Last weekend, guests were treated to sightings of transient orcas hunting for harbor seals in front of Northwestern Glacier on two of our 8.5 Hour Northwestern Fjords trips. We saw the AT1 pod AND the Kodiak Killers, a pod that we have never seen beyond the moraine in Northwestern Fjords Sightings of these orcas are rare and fascinating to witness. Read our blog post about last summer’s transient orca sightings to learn more about what makes these orcas so unique.

Blog post originally published June 19th, 2018

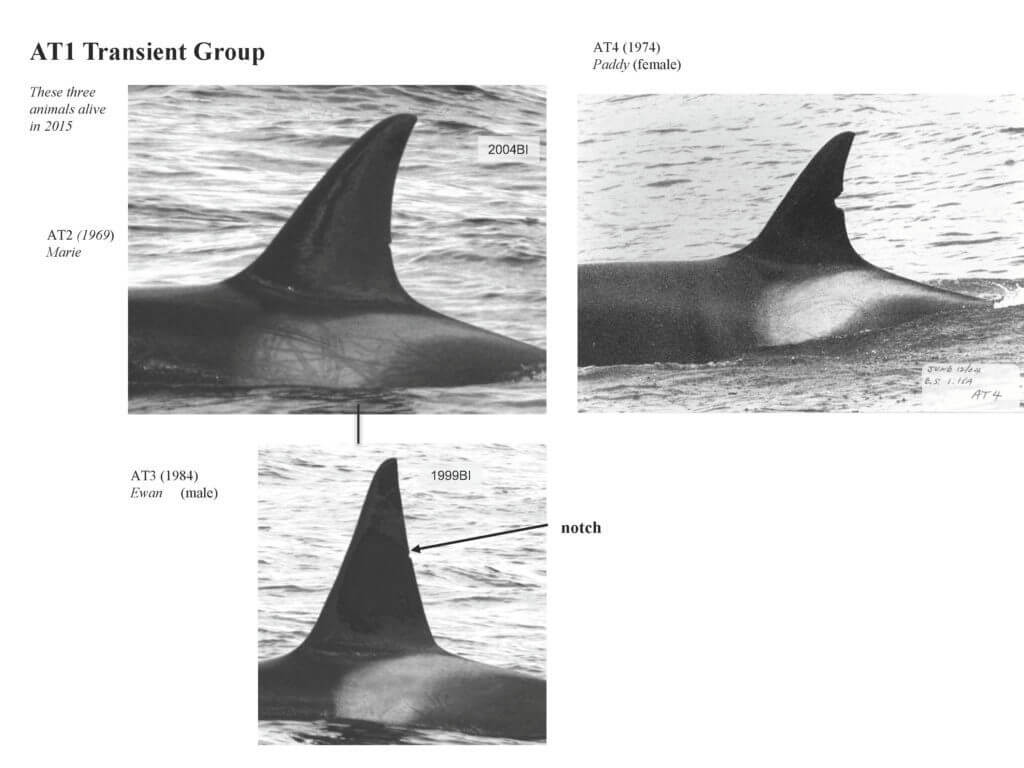

Spencer was the first to spot the black fin. We had just left Aialik glacier’s tumbling blue ice, the harbor seals resting peacefully below on their jagged floats of calved glacier. Captain Justin slowed the Glacier Express along the course of its 7.5 hour trip as we neared the one lone orca, and I trained my binoculars on his dark fin. I traced the wavering curve up towards the breathtaking height of his dorsal fin, the straight drop past a likely notch to a gray saddle patch below: at a glance I knew this was AT6, also called Egagutak, a transient orca from the AT1 pod nicknamed “the lone male” for his solo travels. We had seen no other orca yet, only this single black fin slicing apart the seams of blue water and green coast.

Egagutak’s fin grew and then shrank and then grew again as he surfaced in a smooth line, and then the water went still as he sank out of sight. We knew that we had a wait ahead of us, as transient orca such as AT6 were famous for their long down times and cryptic movements. Feeding on marine mammals such as harbor seals, dall’s porpoise, stellar sea lions and sometimes even larger baleen whales, transient orca move with a higher degree of stealth than their noisy neighbors the resident orca. Unlike the fish-eating residents, the transient’s next meal had the perceptiveness to see them coming.

The water lay a flat blue in the sunshine, so rich in hue that we noticed in a moment the white splash of an agitated harbor seal near the shoreline. I remember how small the seal looked, just a small froth of white water against the immensity of the blue sky and white peaks behind. Then the seal dipped out of view, and there were only fields of colors, blue and brown and green. One second. Two.

And then the surface erupted in a catapult of spray as two dark shapes crashed into view, one the body of AT6, the other the harbor seal silhouetted twenty feet above the surface of the water.

It was over as fast as it had begun. We watched in shock from the Glacier Express, unable to register what we had just witnessed. On the outer decks silence built into an awed murmur. It took only a moment for Egagutak to surface again, circling in quick dives, his feeding hidden from view beneath the powder blue water. After a few minutes a glaucous-winged gull landed on the surface of the water, and then another, and soon the water was thick with the white of gulls snatching unseen fragments from the surface. A bald eagle circled and dipped down to the water with talons outstretched, but flew off with talons empty.

Egagutak had lived up to his role as the apex predator in Alaskan waters. He is also one of only seven remaining orca known to hunt in this glacial environment.

Egagutak is a member of the AT1 pod, and the history of this pod reads as a story of both loss and resilience. The AT1s, or Chugach Transients, are a group of transient orca fully at home in the waters of Southcentral Alaska. They are the only orca ever to have been documented past the vast underwater barriers that compose the moraines of Aialik Glacier and Northwestern Glacier. Navigating their way past the heaps of gravel deposited by a glacial past, the AT1s are able to specialize in hunting the harbor seals that shelter atop the relative safety of glacial ice. They are genetically distinct from all other transient orca, they swim in a far narrower range than other transient orca, and their vocalizations are completely unique to the members of this pod. It could almost be said that these animals speak a language known by no other orca on the planet.

They are also in their final generation.

The story of the AT1s takes us back four decades, to an ecosystem on the cusp of a catastrophic change. At the dawn of 1989, Egagatuk was a young male of the age of thirteen years, a member of the AT1 group that consisted of 22 documented killer whales. The AT1s lived as they always had in the pristine waters, dining on dall’s porpoise and navigating the icy mazes of tidewater glaciers to feast on harbor seals.

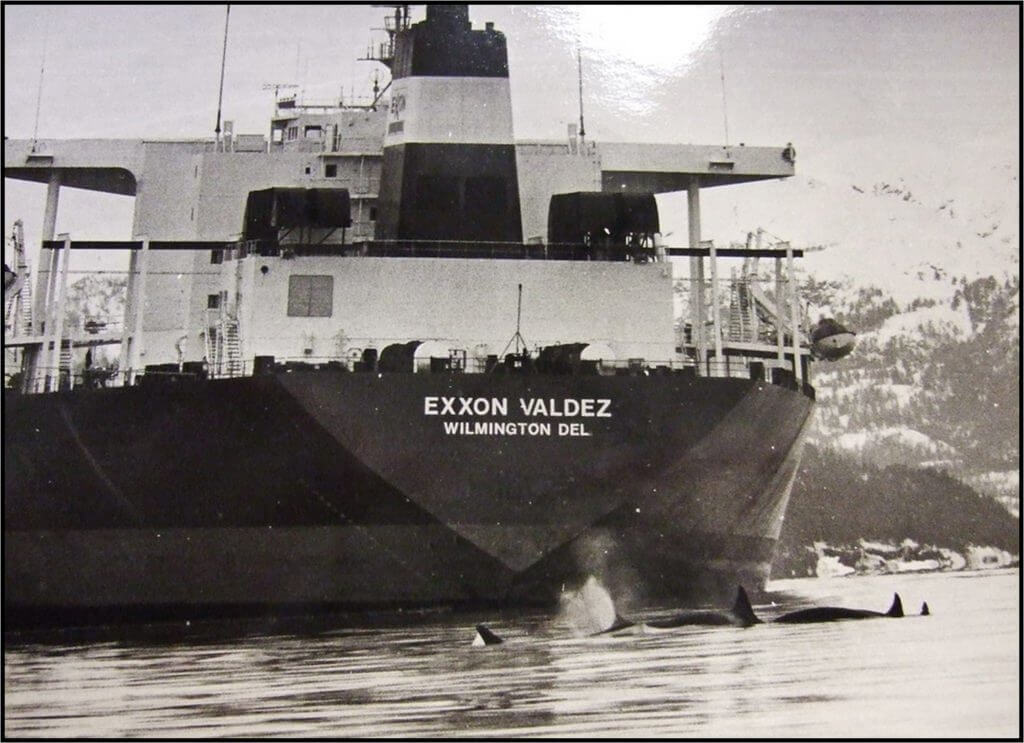

But in March of 1989, the Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef, and the story of the AT1s changed forever. In a matter of days 11 million gallons of oil poured into Alaska waters. A black-and-white photograph taken directly after the spill shows the profile of three dark fins silhouetted against the stern of the Exxon Valdez, fins that have been identified as belonging to members of the AT1s. Within two years of the spill, 11 out of 22 members of the pod had died. In subsequent years 4 other orca went missing or were found stranded. Though today the Exxon Valdez oil spill has long since faded, with these waters returning to their near-pristine state, the spill’s effect on the AT1 pod still remains. Today, only 7 members of the AT1 pod remain. They have not had a calf since 1989.

This is why, when we see Egagutak hunting alone in the icy waters of Aialik Bay, using traditions that have been passed down through the generations, the sight becomes more than just a powerful moment with a powerful predator. It becomes a gift, a glimpse into a disappearing way of life as wild and dynamic as the coastline in which these animals thrived.

And in the month of June, we have had more of these timeless moments than ever before.

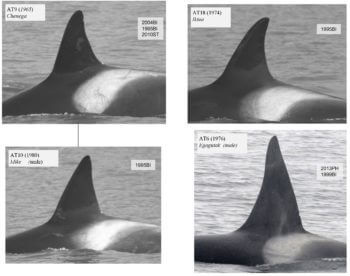

It began with Egagutak catapulting a harbor seal out of the air. Less than a week later, on a 8.5 hour Northwestern trip with Captain Gary, we saw a member of the AT1s known as AT10, or Mike, parting the turbulent currents inside the moraine of Northwestern Glacier. On our return trip a few hours later, we came upon Mike and his mother Chenega, AT9, the matriarch of the AT1s, with another individual that was likely AT18, known as Iktua. The gulls on the surface of the water told the tale of a successful hunt. Chenega and Mike surged through the water side-by-side, likely engaged in the ritual of food-sharing that strengthen the bonds of mothers and sons who will travel together their entire lives.

A few days afterwards I stood on the deck of the Orca Song on a 3.5 hour trip as Captain Kayleigh pointed out the three dark fins moving in tandem across the waters of Resurrection Bay. Chenega, Mike, and Iktua puzzled the water into a geometric series of black triangles. We sat in silence in the calm water, listening to the still surrounding these resilient survivors. It took a moment for the gulls to follow.

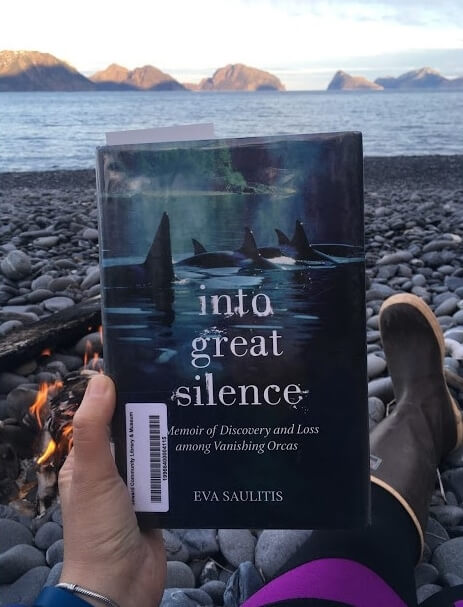

Behind the shapes of the fins, I could make out the coastline of South Beach, where I had sat alone last year beside a tent and a driftwood fire and opened the book that would forever link me to the story of the AT1 transients. Into Great Silence, by Eva Saulitus, is the memoir of a researcher who had studied the AT1s from a remote outpost directly before and after the Exxon Valdez spill. A stirring combination of poignant lyricism and groundbreaking research by a powerfully questioning voice, Into Great Silence is the first book I recommend you read when traveling the Kenai Fjords. The work begun by Eva Saulitus continues to this day through the North Gulf Oceanic Society, where updates about the AT1s can be found on their facebook page. These are the legacies of AT1s, present for a moment longer, immensely precious in both the written stories of their past and the sagas they themselves write upon the sea in voiceless letters of whitewater and gull’s wings.

In the past two weeks, the AT1s have stolen their story out of the ethereal world of books and articles and into the stark reality of dark fins above cold seas. In the month of June we have witnessed at least five successful hunts, as the AT1s feasted both on harbor seals and on dall’s porpoise. Until this June I had never in my life witnessed a successful transient hunt. Now, within two weeks, I have seen three.

Perhaps this means the AT1s will become more familiar visitors to Resurrection Bay and the Kenai Fjords. Perhaps this means more moments with these timeless animals, so special because so rare. Perhaps we will sit on the outer decks above the twisting language spoken by only 7 individuals, watching them move in tandem through the stories they have shared, listening to the silence fuller for their presence on a dive deep below. Perhaps our passengers on Major Marine trips will have more chances to cherish the AT1s this summer. And perhaps this season, you will be here to join us.

Tamara Lang is a senior deckhand with Major Marine Tours in Seward. She is a writer of creative nonfiction and the author of “Upstream: A Written and Photographic Journey up the Los Angeles River.” Her writing and her travels can both can be followed on facebook at Tamara Lang Writes, or at tamaralang.com.

Signup for our newsletter to get the most recent Major Marine updates.